Vietnam — Bảo tàng Chứng tích Chiến tranh (War Remnants Museum), 28 Võ Văn Tần, Phường 6, Quận 3, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam

A sobering experience

September 2015

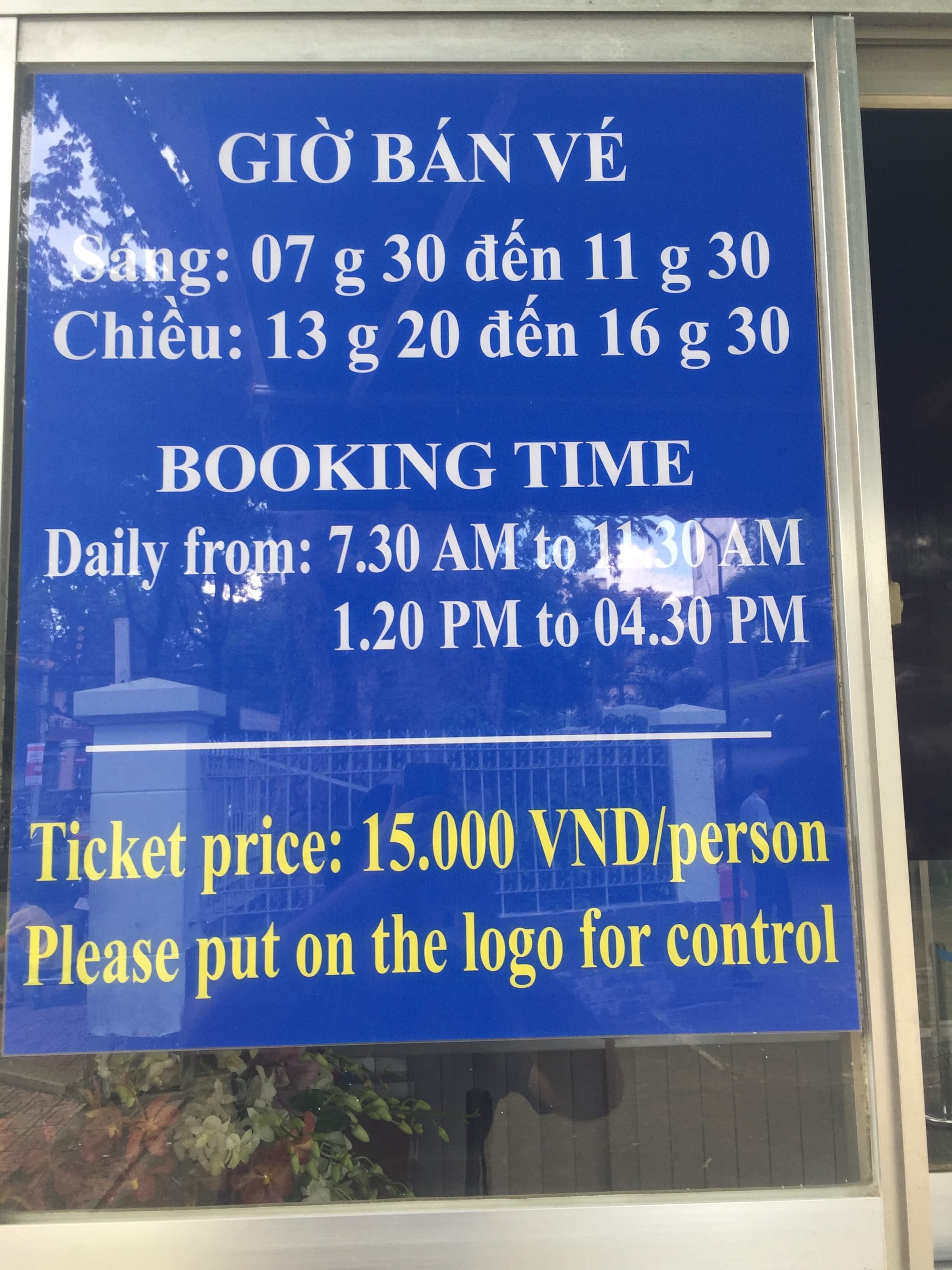

While I was in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam, I decided to visit the Bảo tàng Chứng tích Chiến tranh (War Remnants Museum), 28 Võ Văn Tần, Phường 6, Quận 3, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam. It was a sobering experience.

I spent 2.5 hours at the museum and found it to be harrowing.

Although there are planes, helicopters, and tanks outside the building, don't think the Bảo tàng Chứng tích Chiến tranh (War Remnants Museum) will be one of your standard war museums of 'big toys for big boys' as it isn't. It pulls no punches.

The first clue that this would be a different experience was when a bookseller approached me as I walked in who had lost an eye and both arms to a mine when he was 8.

From there, I went on to look at the 'toys' in the front yard. What amazed me about the hardware was how poorly, almost crudely, constructed it appeared.

After the 'toys’, it was straight into a reconstructed torture prison from Phu Quoc, which also contained a guillotine shipped in by the French and used to behead prisoners.

After the yard, I went to the main building. I started at the top and worked my way down.

The ‘inside’ museum was a museum of photography. There were some exhibits, but not many, and wow, the photographs were powerful. They pulled no punches; it was some of the most moving, powerful, and graphic work I have ever seen.

My tour started with one of the most shocking and best photographic exhibitions I have ever seen, which was only spoilt by poor lighting that reflected off the glass in front of the prints. The exhibition was called "Requiem" and was put together by Tim Page and Horst Faas, two photographers injured during the Vietnam War. The exhibition commemorated all the press photographers who died during the war.

Tim Page and Horst Faas collected thousands of photos taken by 134 photographers who were killed. The exhibition consisted of photographs taken by 83 Vietnamese, 16 Americans, 12 French, 4 Japanese, and Australia, Austria, England, Germany, Switzerland, Singapore and Cambodia, and photo-journalists who were killed. Several photographs were the ‘last ever taken’ by a particular photographer.

There was a list of non-Vietnamese photographers killed:

- Australia: Alan Hirons

- Austria: Georg Gensluckner.

- Britain: Larry Burrows, James Denis Gill.

- Cambodia: Chea Ho, Chhim Sarath, Chhor Vuthi, Heng Ho, Kim Savath, Kuoy Sarun, Lanh Daunh Rar, Lek, Leng, Ly Eng, Lyng Nhan, Pen, Put Sophan, Saing Hel, Sou Vichith, Sun Heang, Tea Kim Heang, Thong Veasna, Ty Many, Vantha.

- Germany: Dieter Bellendorf.

- United States: Robert Capa, Sam Castan, Dickey Chapelle, Charles Richard Eggleston, Robert Jackson Ellison, Sean Flynn, Ronald D. Gallagher, Neil K. Hulbert, Bernard Kolenberg, Oliver E. Noonan, Kent Potter, Everette Dixie Reese, Terry Reynolds, Jerry A. Rose, Dana Stone, Peter Ronald Van Thiel.

- France: Claude Arpin-Pont, Francis Bailly, Gilles Caron, Franz Dalma, Bernard B. Fall, Gerard Hebert, Henri Huet, Pierre Jahan, Michel Laurent, Raymond Martinoff, Jean Peraud, François Sully.

- Japan: Taizo Ichinose, Hiromichi Mine, Keizaburo Shimamoto; Kyoichi Sawada.

- Singapore: Charles Chellappah, Terrence Khoo, Sam Kai Faye.

- Switzerland: Willy Mettler.

And one name jumped out at me — Robert Capa — I had studied his work as part of a photography course.

I had seen many of the images before and heard of some of the photographers. The pictures made by Larry Burrows were extraordinary.

As I moved down the building from room to room, I encountered more shocking images of war. We moved away from the pictures chronicling war and the combatants, to those recording the results and the aftermath, particularly on civilians. These images were shocking, and the exhibition showing photographs of deformities caused by defoliants such as Agent Orange were very graphic.

I must admit that I came out after 2.5 hours feeling quite depressed by the whole experience but don't let that put you off as it is a museum that needs to be experienced first-hand, and that is why I have no images taken inside the building or of the memorials. You need to experience them.

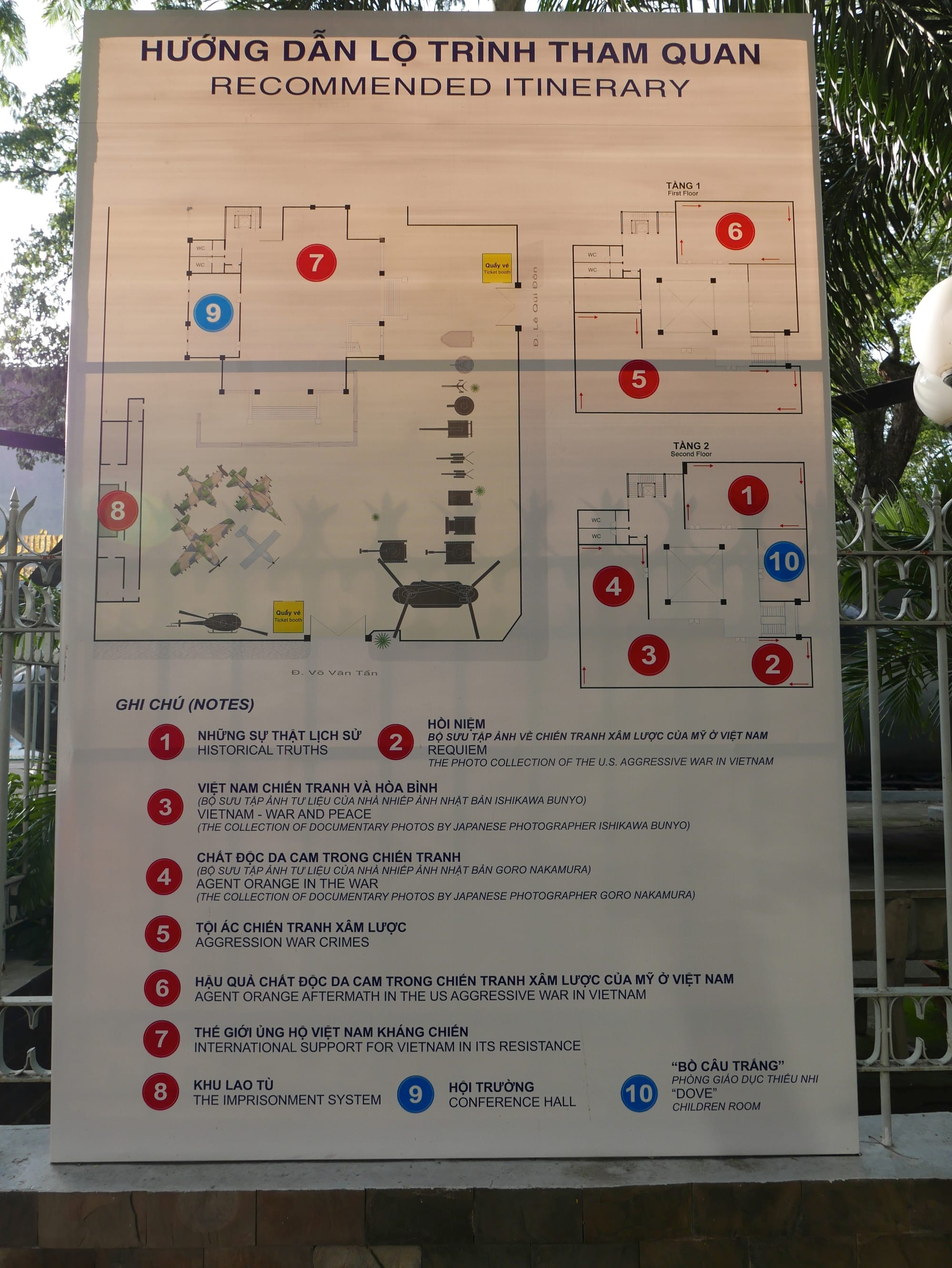

There was a recommended route to explore the museum.

The museum had an impressive number of exhibits crammed into a small building and yard.

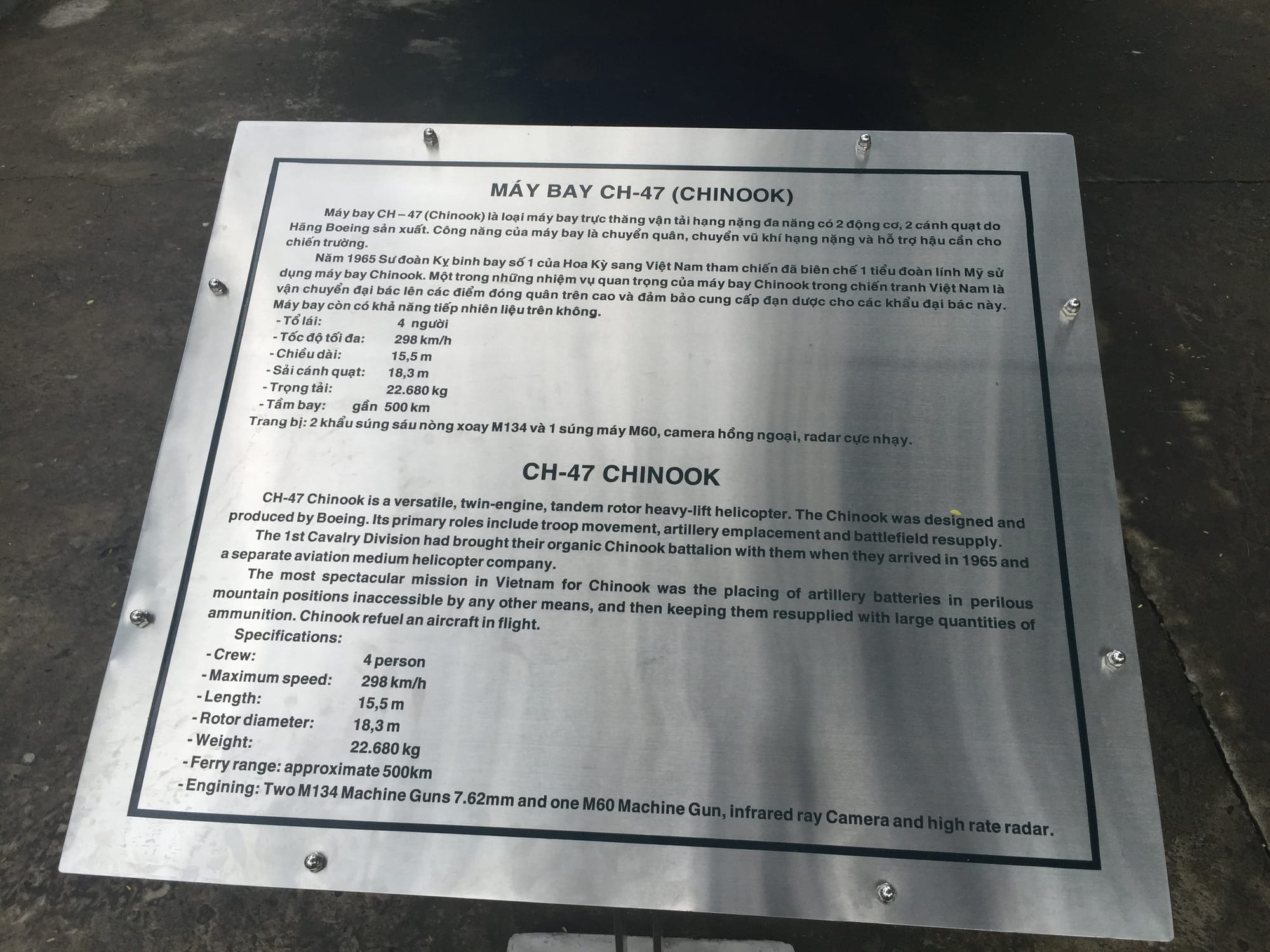

There was a classic CH47-Chinnok.

The Chinook was first brought into Vietnam in 1965 by the 1st Cavalry Division. These helicopters were used at one point in the war to place American artillery batteries on top of inaccessible mountains.

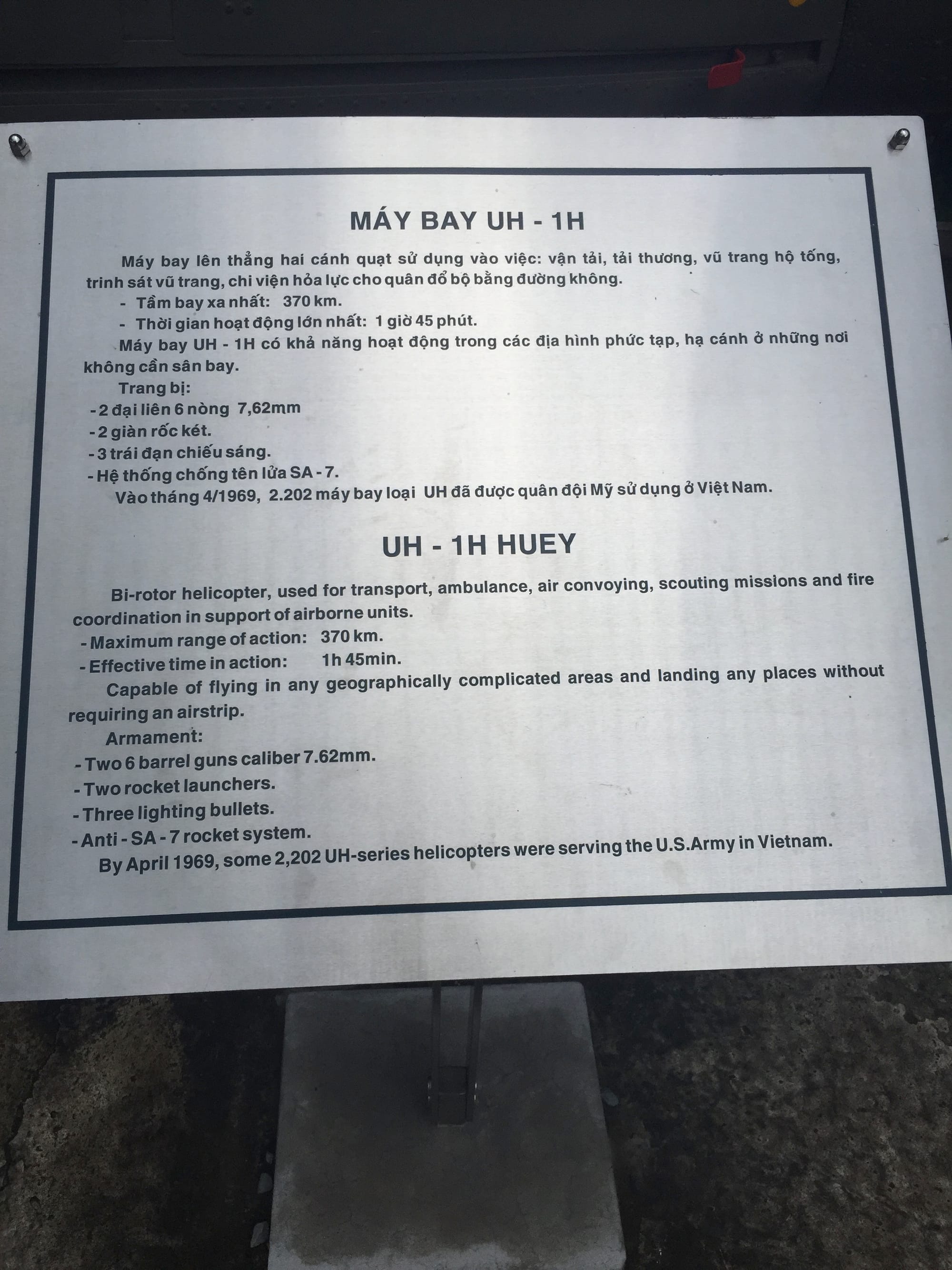

Another classic helicopter from the Vietnam War — the Huey.

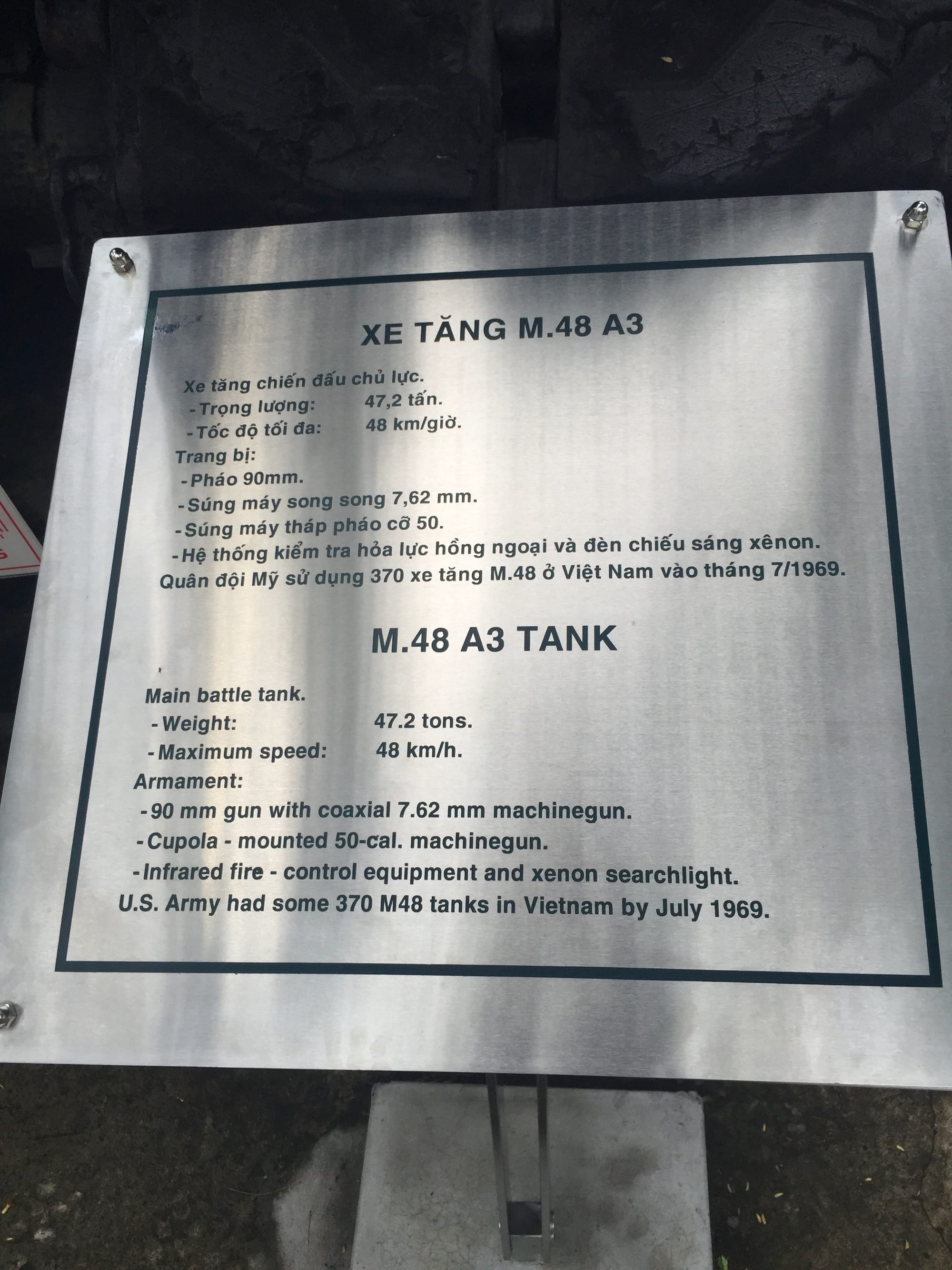

I don’t associate tanks with the Vietnam War, yet the US Army had around 370 M.48 A3 Tanks in Vietnam in 1969.

The classic US Army logo.

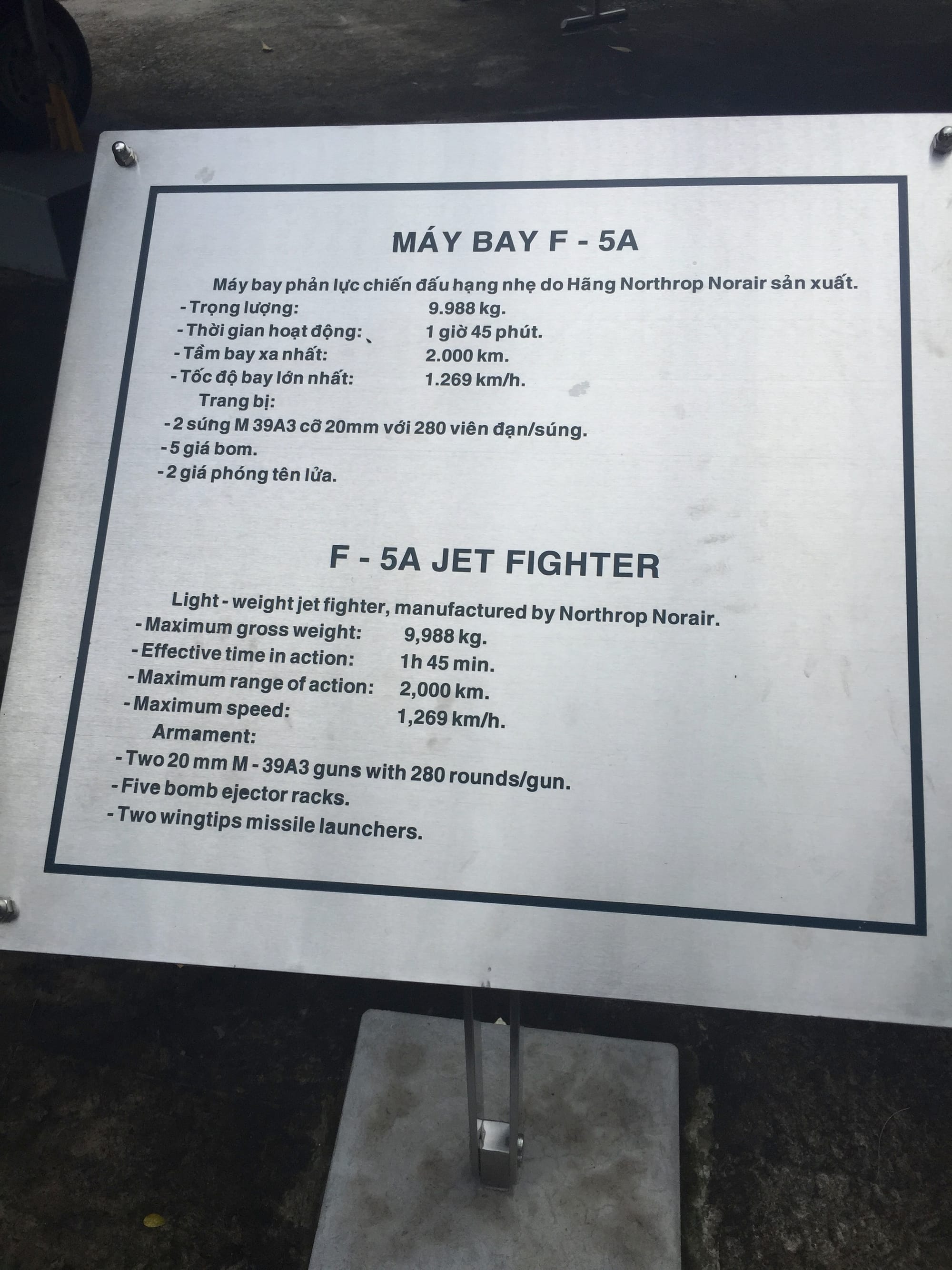

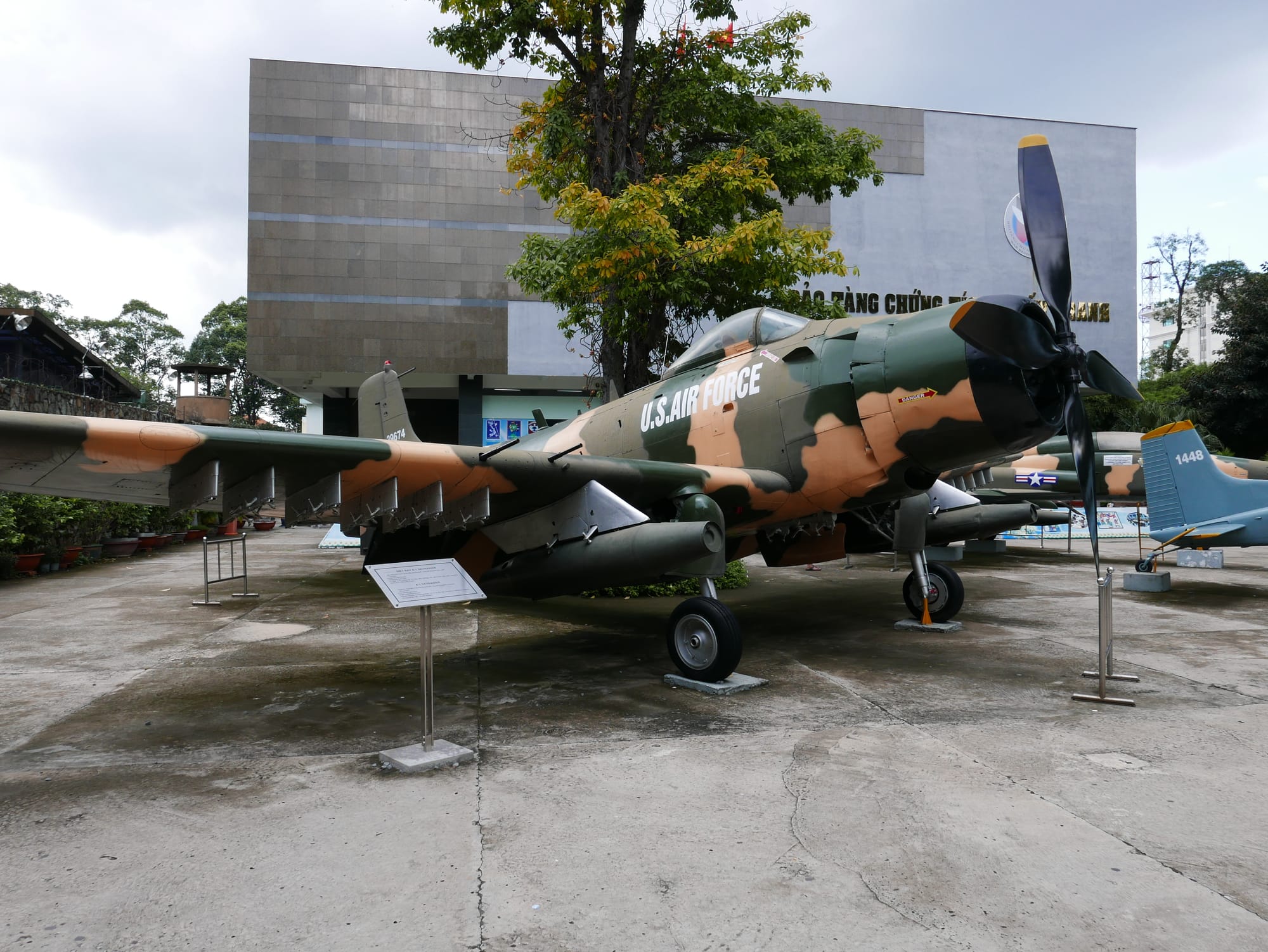

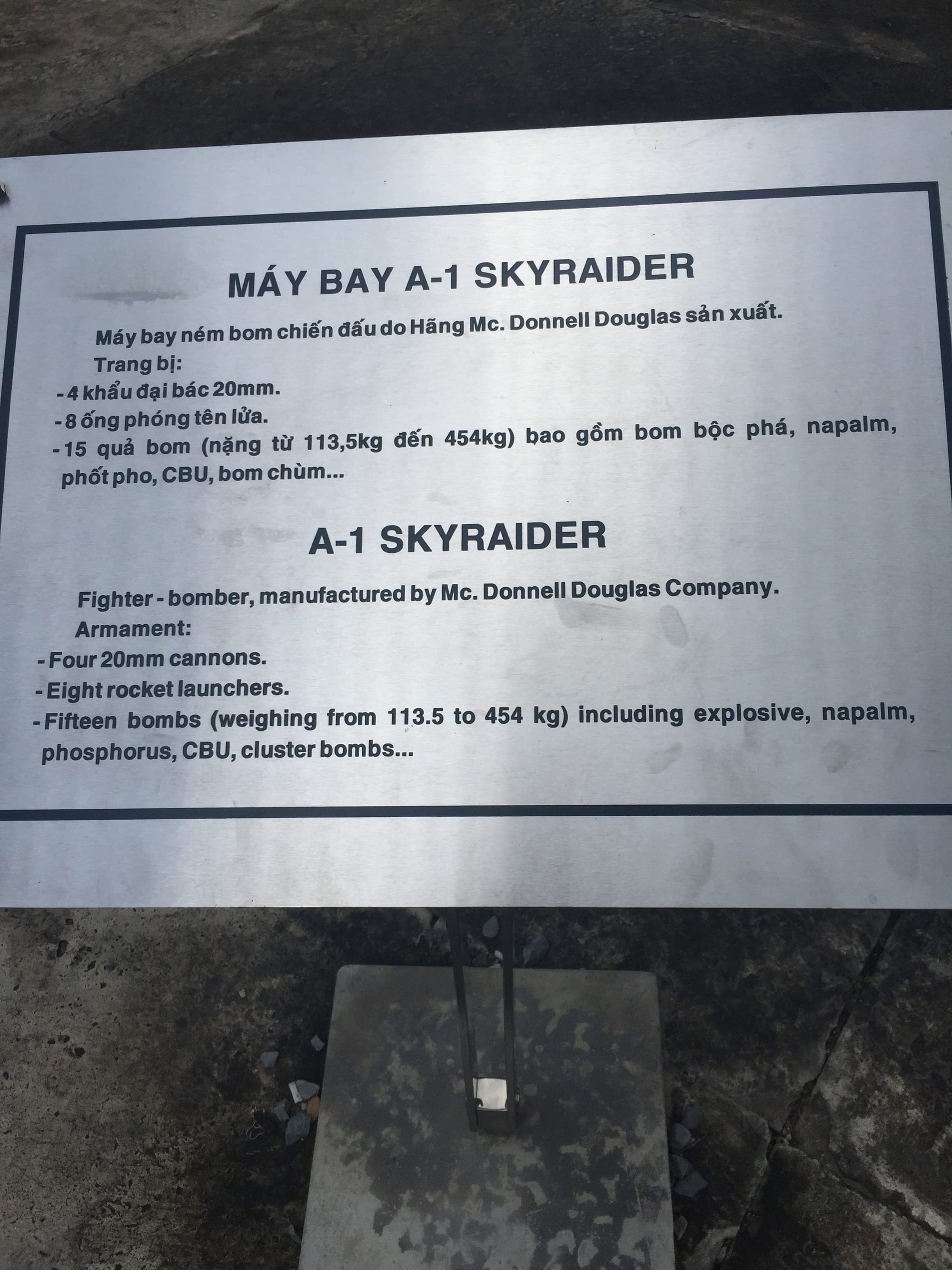

There were also examples of some of the aircraft used by the US on display, including the F-5A Fighter and the A-1 Skyraider.

In one corner of the museum was a collection of bombs and shells used by the US during the war.

The museum also explored how Vietnamese prisoners were treated by the French and the Americans, and numerous first-hand accounts were available at the museum.

The French brought the guillotine to Vietnam in the early 20th century and used it in a jail on La Grandière Street (now Ly Tu Trong Street). During the Vietnam War, the guillotine was used until 1960, when the last man was executed — Mr Hong Le Kha.

The museum also contains a memorial to Vietnamese prisoners held at the Phu Quoc Prison, and it made for some terrifying reading.

From the information boards in the museum — Phu Quoc is the biggest island in Vietnam, with an area of 573 km². The island is in the Kien Giang Province and is 85 sea miles from Rach Gia.

In 1953, the French colonists built the “Cay Dua Prison Camp” (Coconut Tree Prison Camp) on the south of the island to house 14,000 prisoners of war.

In 1956, the Saigon government rebuilt the prison camp into the Cay Dua Political Correctness Camp to hold political prisoners moved from Bien Hoa Political Correctness Centre. This camp operated until March 1957, after which a new, bigger prison was built — Phu Quoc Prisoner of War Camp, which officially operated from July 6th, 1967.

From the information presented, it was unclear what the prison was used for from 1957 to 1967.

The Phu Quoc Prisoner of War Camp was divided into 12 areas and held 40,000 prisoners. Each area was divided into nine sub-areas, and each division had 11 cells. These areas were surrounded by barbed wires and watch towers with floodlights.

Some 4,000 prisoners died in the prison.

According to the information presented, the Phu Quoc Communist Prison was the biggest American prison in Vietnam. It was said to be a "hell on earth" (Mr Pham Ba Lu, Head of the Board of Communication for ex-Phu Quoc Prisoners at a meeting on the Phu Quoc Prisons at War Remnants Museum on December 15th, 2008.) The prison was known for torturing and mistreating the inmates.

The information, first-hand accounts, and testimonies in the ‘Imprisonment System’ part of the museum (part 8 of the itinerary) made for a very sobering, depressing and alarming reading.

As I said at the start, I spent 2.5 hours at the museum and found it harrowing. But don’t let that put you off, as it was an experience I won’t forget, and I am glad I visited.

Foursquare: Bảo tàng Chứng tích Chiến tranh (War Remnants Museum)